Paul Townley-Smith, Director of Design & Prototyping, ZYGO Electro Optics

Many products need optics, but very often doing the optics yourself is not an attractive option.

For the reader, we mean ‘doing optics’ to be optical physics, optical design, optical components, optical systems, assembly best practices, and in general all encompassing aspects of the knowledge necessary to repeatedly produce an optical system which performs as designed.

Optics is a niche technology that does not have a lot of crossover with broader domains such as electronics and software. Thus, to successfully manufacture optics internally requires a significant commitment to an optics infrastructure that cannot be repurposed for other tasks.

There are plenty of situations where you need a partner instead of doing optics yourself:

- Your core product is an algorithm or a complex system and optics are a critical but small part of the product value.

- You need to move quickly and don’t have time to organically grow an internal optics organization.

- Yours is a new product with uncertain growth potential so you can’t or don’t want to make a large investment in optical infrastructure.

- You need to design the right optical system once to get the product going but the ongoing needs are too infrequent to justify an ongoing internal organization.

- Your volume is too small to do the optics manufacturing efficiently.

- You are an expert optical theorist who can design a high performing system, which has zero chance of being manufacturable

So, when you find yourself in any of these situations, what you need is a partner that specializes in optics that can deliver the systems you need at prices you can afford. The right kind of partner is a partner you can trust, who understands how to collaborate effectively, and has the right processes in place to get the job done.

A WORD ABOUT PARTNERSHIP

When using a sub-contract specialist company for the design, development, and manufacture of electro optical (EO) devices and components, the word “partnership” is over-used. Many who do use it don’t fulfill its promise —what on the surface seems like an equal collaboration is actually just a series of transactions. But the rare well-functioning partnership between supplier and customer can make or break an efficient product development process.

Some customers are intimidated by the concept of partnership. There is a perception that partnership means “lock-in” once the project moves beyond design and development and into manufacturing. But if you are working with a supplier that exhibits an open, honest, and trust-worthy approach to relationship and pricing, you can avoid trepidation about what will happen in the next development phase. The real meaning of “partnership” can be fulfilled, with clear expectations and communications, the right match of experience for your application, and strong program management and processes to keep things on track.

- Technical illustration of modern dual-camera system for smartphone. Internal circuit of device on light background. Service concept. 3D Rendering

TRUST

The upsides of trust in the supplier/customer relationship are obvious. But equally important are the downsides and wasted time when there is doubt. A good supplier/customer relationship means collaborating with eyes firmly on the prize, rather than getting bogged down in details of contract terms trying to protect every foreseeable difficulty. A lack of trust can create the worst case scenario, a transaction-oriented relationship where the customer owns the design internally (without the requisite skills to support it) and attempts to use the supplier as a commodity job shop to reduce dependency. In this kind of relationship there is no commitment, no buy-in, and both sides constantly struggle to “win” in the next contract negotiation.

When approaching the subject of trust, it is perhaps appropriate to view your chosen EO device supplier as a consulting business rather than a manufacturing business. In this way, when looking to engage with a supplier, the initial interactions should be about ways of working, expertise, and trust. If instead you view the supplier as a manufacturing business, the focus will immediately be on technical parameters, “feeds and speeds”, and lists of technical specs that confirm capabilities alone, and which customers are typically not expert enough to properly assess anyhow.

So customers should ask themselves two key questions.

- Can I trust that my partner will protect my interests (even when I’m not looking)? This aspect of trust is about values, and should be of great concern for customers because the follow-on manufacturing creates a long term inter-dependency that would not be part of a typical one-off consulting engagement. Will the supplier be honest with you when they screw up? Will they inform you of problems that affect you before it’s too late to do anything about it?

- Can I trust my partner to do the job well? This is about competence. Does the partner possess the right skills, capabilities, and experience to get the solutions you need? Can the partner convince you that no matter how difficult the problems may be, they have the right talent on the team to solve them quickly? Can the partner create designs appropriate to your needs, not over designed (too expensive) or under designed (which fails in the field)? Does the supplier have process and discipline to meet published schedules?

COLLABORATION

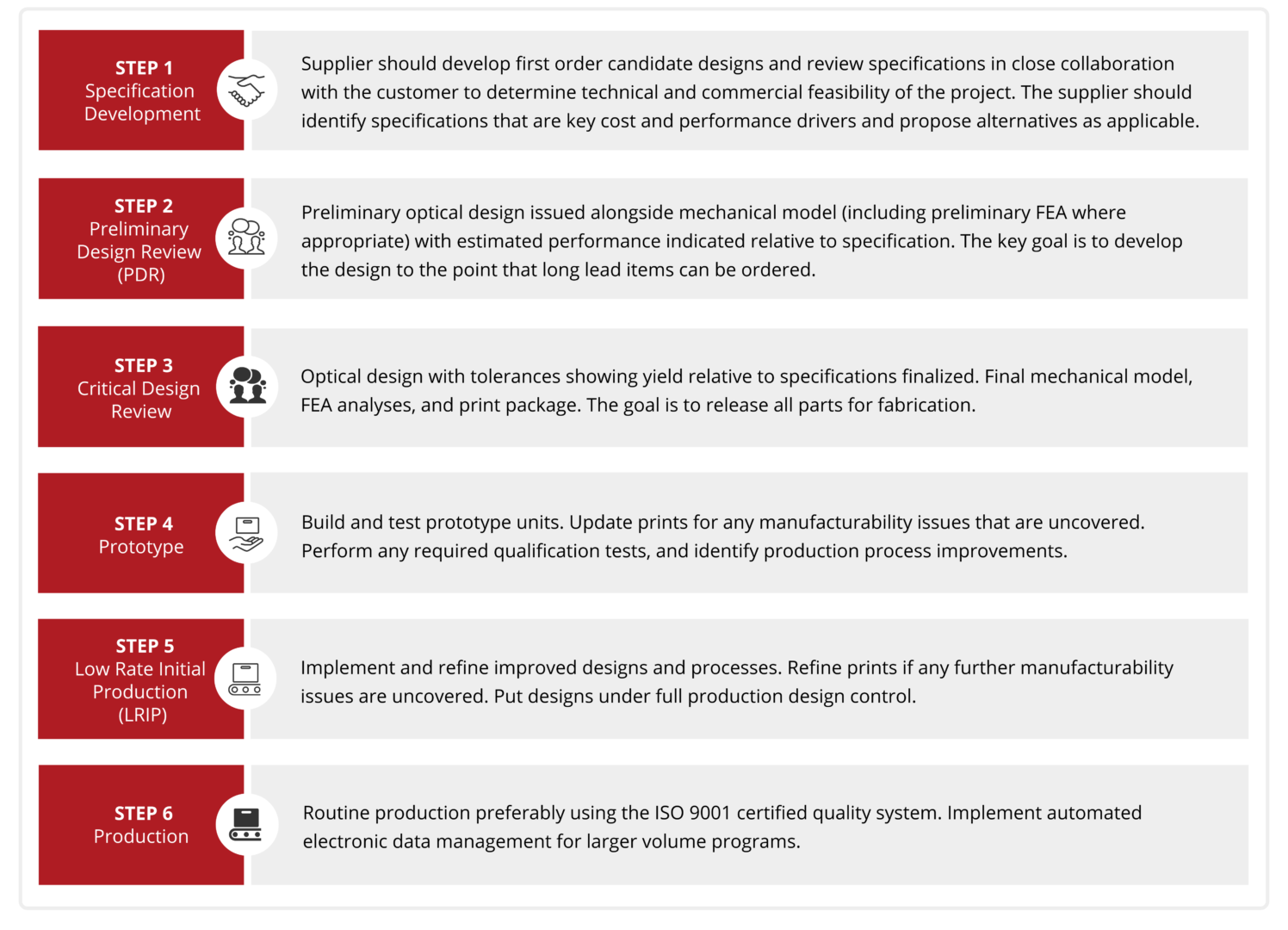

Collaboration is easy to claim, but the only way of proving it is to demonstrate it, so ask your supplier for testimonials or details of past projects. A good partner should have a standard process for product development that is set out and explained to customers, so they know what to expect and why it is done the way it is. Then the supplier should follow that process in a disciplined manner.

How about checking to see if your short-listed supplier publishes a detailed schedule that includes the key milestones of its standard process? In the middle of the design effort, suppliers should formally discuss progress directly with your engineers, not through intermediaries. This helps your team get the real information and not something filtered by a salesperson or financials-focused manager.

When reputable suppliers run into problems, they should work quickly to develop a set of options for the customer, then contact the customer, explain the situation and the proposed solutions, and decide on a plan update together. Much of being seen as open and collaborative is about attitude and style. If the communication style is indirect — mediated by salespeople, full of spin, and highly selective in the details — customers won’t

have the opportunity to build a trusting relationship with their supplier.

In other words, “open and collaborative” is not so much what suppliers do but “how” they do it. To be seen as open and collaborative, suppliers have to engage the customer in direct conversation, speak clearly and frankly, and acknowledge risks and unknowns (along with the plans to mitigate). And right from day one, suppliers must follow through on everything they say they are going to do.

PROCESSES — MANAGING PROGRAMS

It is certainly worth interrogating a potential supplier about how they manage programs, and suppliers should follow a standard process to get from idea to finished product. The schedule should be published as an MS project document or equivalent and should typically be reviewed and updated on a weekly basis (see below).

A typical 6 step workflow.

PROCESSES — DETAILS, DETAILS

There is no definitive list of questions to ask your short-listed supplier, but you should seek to get a handle on the number of designers, engineers, and production technicians that are in-house with the relevant expertise and experience for your project, and what surge capacity can be accessed. Also, you should assess the financial robustness of your chosen supplier, as this will also affect the maturity and robustness of low-cost supply chain materials such as glass and metal as well as whether they will survive economic lows.

Another issue to tease out — how does your chosen supplier transition products from design to manufacturing? The product development team should start to get involved in the project around the time of the preliminary design review (PDR). This team should develop a parts tree, sketch out an assembly procedure, compose an acceptance test plan, and produce preliminary travelers to manage production data. These documents should be refined as the product progresses through design, and are then used to build prototypes and procedures, and traveler data requirements are updated to reflect what was learned in prototyping.

Also, ask about the supplier’s approach to product verification and validation. Some suppliers will offer “by design” estimates or “let’s try it and see” when facing measurement challenges. Ideally, a supplier should have the capability to develop custom test methods and equipment for truly validating critical specifications. Examples could include measuring MTF over temperature and altitude, at-wavelength interferometry, ppm distortion, and validated gravity compensation for systems with large optics.

Checking out the supplier’s limits at the high end are always quite revealing about the sophistication of their processes. Best-in class suppliers can produce surfaces and low stress mounting suitable for extreme ultraviolet (EUV) applications — the most challenging commercial application for optics. Can the supplier align lens TIR and airspace to ~1μm of error? Can they design and manufacture athermal systems that operate over a temperature range of -25°C to 65°C?

Finally, you need to get a fix on whether the supplier has experience of applications similar to the one that you are working on. Ask how many times they have taken a product from idea to production, the breadth of industry sectors served, and the sort of applications in each.